26 Mar Winding Road

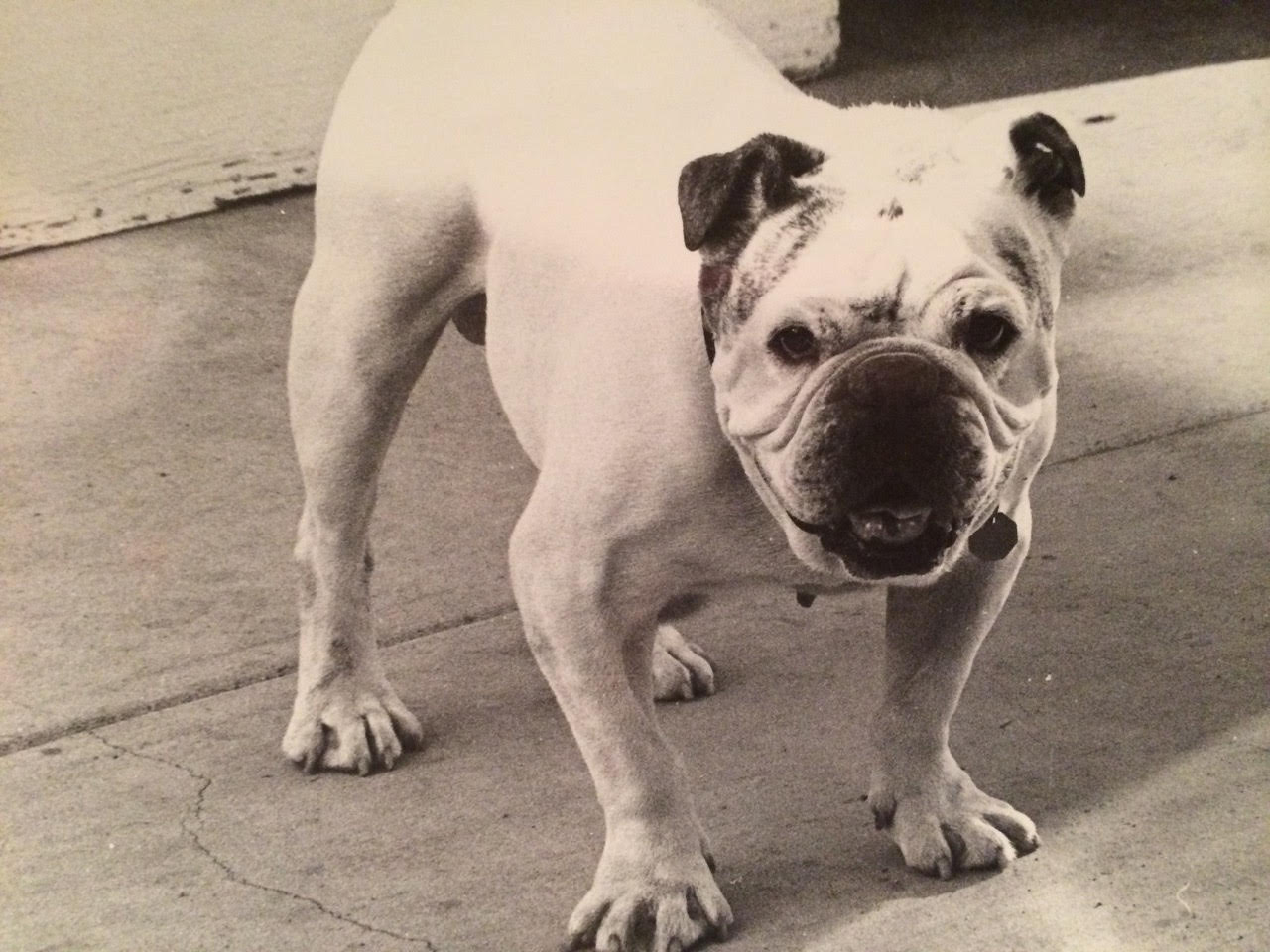

I always remember writing. I didn’t think much of it; it was just something I did. I published my first article when my beloved third-grade teacher, an elderly lady with big sunburst brooches, suggested I write an article about the death of my bulldog, Oliver, for a local pet lovers’ newsletter. (This, in the day when newsletters actually arrived in your mailbox.) It was very dramatic (“Was this my dog, my Oliver, that was dead? No! No, not my dog! Not my Oliver!”) and they published it with a byline and my picture a few months later.

I won a couple of young authors contests after that with poetry inspired by Shel Silverstein and a school short story contest in high school. I wrote incessantly—particularly in class when I was bored—and I loved to read, but my passion was ballet. I sewed ribbons on pointe shoes during school lunch breaks, did homework in the car while shuttling an hour away from Lincoln to dance with the Omaha Ballet, spent my summers in Kansas City, Illinois, and New York.

I won a couple of young authors contests after that with poetry inspired by Shel Silverstein and a school short story contest in high school. I wrote incessantly—particularly in class when I was bored—and I loved to read, but my passion was ballet. I sewed ribbons on pointe shoes during school lunch breaks, did homework in the car while shuttling an hour away from Lincoln to dance with the Omaha Ballet, spent my summers in Kansas City, Illinois, and New York.

My dream of permanently gnarled toes got sidelined when I tore a groin at fourteen. And though I continued to dance, my professional dreams, I knew, were over.

Back home during spring break my freshman year at Smith College, I was talking with my dad about that summer’s plans, which consisted of studying economics abroad and working at a bank. It was assumed for a while that I’d eventually join an ad agency or maybe become a news anchor (I really don’t know why). But during that talk, I blurted: “I really want to write a novel.” I had loved the emotional ride of favorite books like Clan of the Cave Bear and wanted to see if I could create something for another reader to enjoy.

Dad, by then an author of some thirty academic books, said, “Okay. I’ll make you a deal. I’ll pay you what you would have made at the bank if you put the time you would have spent working there into writing a novel.”

So I spent my spare time at Oxford that summer gathering information on the Neolithic Stonehenge people and preparing to write an epic historical novel.

I had no idea what I was getting myself into. Somehow I would have to figure out who these people were, what they wore and ate, whom they worshipped, and what their stories were. I read an entire suitcase worth of books, highlighter in hand. I printed a sparse outline on my dot matrix printer and laid it alongside a pile of research notes, more or less organized by category, on one long, continuous ream of perforated printer paper.

I typed the whole thing on the “portable” (“trans-portable,” Dad and I always joked) PC I had lugged all the way to college and back for the summer, with its tiny six-inch screen in WordStar.

It was hard. I didn’t know what should happen from one chapter to the next. Had to figure out how to incorporate all these precious research details into a narrative I constructed as mechanically as a house. I ate chicken salad sandwiches and pecked away at the keyboard of the trans-portable PC on my bedroom desk while friends went to the pool.

But at least I wasn’t working at the bank.

It took me two summers to finish that book, which I dramatically titled Twilight of the Ancients and packed off to Writer’s House—bound with an illustrated cover and 23-page synopsis—seeking representation.

I was soundly rejected. But in the course of the reader’s two-page analysis—a gift in itself—about the two-dimensional quality of my characters, lack of story tension, and unclear and unanswered story questions, a single line stood out to me:

“…comparable to Clan of the Cave Bear”

Never mind that I had made every newbie mistake known to man in my submission, that the book itself was one long 360-page exercise in how not to write a novel. The reader had compared me to Clan of the Cave Bear.

I was hooked. I was going to become a novelist.

But not right away.

I wrote for two years on the staff of Smart Computing magazine after college, during which time I also wrote two computer books. It wasn’t what I dreamed of doing, but it was paid writing—which I assumed made me a professional—and I learned a lot.

I first got the idea for Demon: A Memoir in 1998 while driving home on a hypnotizing stretch of Nebraska road. I was in the middle of another project, a fantasy novel about a woman warrior I had (non)affectionately named The Book That Will Kill Me, if only because I had spent years writing and re-writing the first 100 pages. (Yet another error I learned the hard way.)

I jotted down the idea of a demon telling his story, planning to revisit it someday after I had vanquished the Book That Will Kill Me.

“Some day” turned out to be only a few hours later when my motherboard short-circuited as I sat down to write. It fizzled and popped inside the case, a tiny wisp of smoke drifting out the vent. I sulked out to the sofa with notepad and paper, determined to march on.

Nothing came. At last, I flipped the page and began to write this demon idea. The story that would become Demon: A Memoir was finished six weeks later.

Behold, The Book That Will Kill Me gave way to The Book That Was Meant to Be.

Or so I thought.

At some point during the six years I waited for Demon to sell, I randomly penned a single page in the voice of the earth’s first woman. I imagined her nearly 900 years old and near death, preparing at last to tell her full story. And then I put the page away in a drawer where I kept scribbles and random story notes and forgot about it.

In 2004, I ran into local author Steph Whitson at the day spa.

“How’s the writing?” she asked.

I think I grunted.

A few weeks later she sent me a newsletter (the bonafide, printed kind) with an article circled. A new imprint, looking for books exactly like Demon.

My shiny new agent sent Demon off and two weeks later, the editor wrote to say he wanted it.

And then he left the imprint.

Several months and much hand-wringing later, the same editor sent it to committee at his new publishing house. They decided they wanted it—if I could rewrite the entire thing.

I didn’t think I could—didn’t know how. I balked, stymied.

And then I rewrote it.

While negotiating the sale of Demon, my soon-to-be-editor asked what else I had. I looked blankly around, phone to my ear, and yanked open my drawer of scribbles. “I have this!” I said, pulling out the fringed notebook page about Eve. The house bought Demon in a three-book deal and I set to work writing Havah: The Story of Eve.

For the second time in my writing life, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. A year later, Genesis commentaries, horticulture textbooks, books on ancient farming, early weapons, textiles, basket weaving, brick-making, and early civilizations littered my floor alongside a copy of What to Expect When You’re Expecting.

I was fascinated with the emotional journey of Adam and Eve, with the potential for tension between the alpha Adam and his first son, the idea of seeing a first infant, the first death, the first enmity between human and animal and dysfunction in relationship.

But there was a problem. I was paralyzed by Demon’s early success, which had garnered strong reviews and award nominations in the first months of its release. And here I was, about to prove myself a one-hit wonder.

I chased Eve’s story in a dogged panic and overwrote the first draft by 67,000 words (about 260 pages).

Some time after Havah released with a starred review from Publishers Weekly, a reviewer compared it to Clan of the Cave Bear in all the best ways.

That was a sweet, sweet day.

Goodness Onaimu Aliu

Posted at 02:13h, 14 MayYour resilience is something!

Thank you for this piece. It’s the first time I’m reading any of your works and I must say I’m pretty impressed.

I look forward to digesting your works.

Rebecca Johnston

Posted at 19:55h, 29 MarchI wonder often when reading this if you ever considered giving up. This is the point I say, “Thank God she didn’t stop.” I will be 77 Sept. 7, 2024. So if I have read all of your books 2-3 times, and I am rapidly reaching the point of having to read last nights chapters again the next day. Which frankly is a little heartbreaking. So if writing the next book does gets too overwhelming, please dig this posting out and do it for you, and for me.

Love Becky

Rebecca Johnston

Posted at 19:16h, 29 MarchWell that was very cool to read. Have YOU EVER SAID I CANNOT DO THIS.? Evidently this is where I say Thank God you didn’t. I will be 77 in September. You need to start thinking Dang I gotta get her some books in the pipeline while she can still follow them and doesn’t have to read them over and over to make them stick